Porn, fist-fights and ASMR: What's English class like at a low-income high school?

I spoke to seven South Aucklanders who attended decile-one high schools about their reading habits and experiences in English class.

Joseph* regaled me with the incident that caused his high-school English teacher to resign in despair. “We were playing dodgeball in the class using the tables and chairs,” the 27-year-old support worker told me. “Someone would stand up at the front of the class where the whiteboard is, and everyone would just throw a chair or a table. What do you call that, dodge-table, dodge-chair?”

His teacher, Mr. L—, a kind-natured Jewish man, was powerless to stop the chaos, and quit soon after. “It was pretty bad,” Joseph continued. “Looking back at it, it was pretty bad.”

Joseph said it wasn’t unusual for fights to break out in English class: student-on-student, and even student-on-teacher. “We had some crazy kids at school. I remember this fob kid beat up one of the teachers just because she got told off. Just violent kids that don’t really care, you know? They don’t care for consequences.”

The teachers were almost comically out of their depth when it came to this kind of violence, Joseph added. “[My friend] had a fight with some Māori kid, he got a hiding. Teacher’s just standing there. He’s just half-heartedly sticking his arms out.” At this point in our conversation, Joseph affected a nasal, white-guy accent: “‘Hey guys, stop guys.’ That’s the Jewish guy, Mr. L—, he was honestly really nice. Too nice for that school.”

Why don’t young people, and young men in particular, read for pleasure anymore? There’s so much chatter about this topic in news media and on my corner of Substack, and data behind the handwringing: a slew of studies in the past decade show young people spend less time reading for pleasure than previous generations. Why? A range of reasons crop up: books can’t compete with the dazzle of video games and Reels, the publishing world is dominated by women who write flat male characters, prestige TV is the new novel, and so on.

I wanted to get the non-reader experience from the horse’s mouth, and I’m particularly interested in the perspectives of people who grew up without a lot of money or cultural capital, so I’ve been chatting to Joseph and six other interviewees between the ages of 17 and 30 who attended decile-one schools in South Auckland—for international readers, that means the poorest schools in a poor area of New Zealand—about their reading habits and experiences in high school English.

‘Good luck getting an Islander parent to read you a book at night’

None of my interviewees habitually read for pleasure. Most have no interest in reading, and didn’t when they were kids either. “I hated books, I hated reading. Always,” Joseph said. “It’s boring, eh? Just reading words.”

Did any adults attempt to instil a love of reading in childhood? For most of my interviewees, the answer was a flat no. “Good luck getting an Islander parent to read you a book at night,” said Joseph, who is Samoan but born and raised in New Zealand. “That’s a white or an Asian thing, you know? Bedtime stories and shit. We don’t do that.”

“Was I ever read to? Nah.” This is Lui, a 27-year-old healthcare worker who grew up in Samoa and immigrated to New Zealand aged nine. He said the only book in the house growing up was a Bible, which no one read—“it was just sitting there.” His experience was typical of a Pacific Island childhood, he told me, and research supports him: a 2017 study of Tongan families found that around 70% of kids had “nothing to read at home”, and even among those who did, the materials were often not suitable for their age or written in a language they didn’t know.

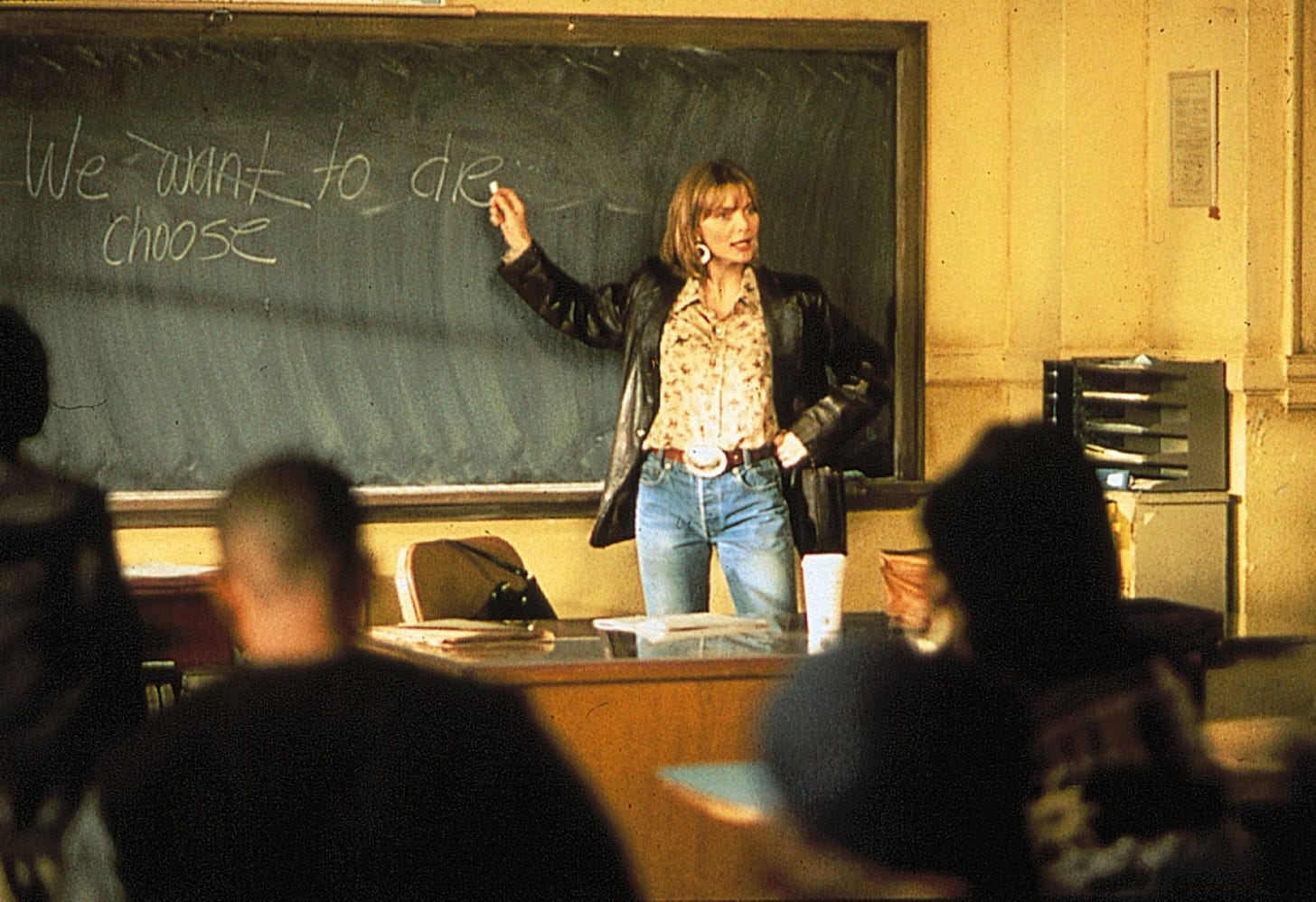

What about high school English class? If you don’t grow up in a home with books, surely this is the next best place to get a taste of the joys of literature. Did any do-gooder teachers like Michelle Pfeiffer’s character in Dangerous Minds flip the chair around, cap backwards, and speak to my interviewees about the value and pleasure of reading? Did they encounter any shrewd risk-takers willing to reach them where they lived emotionally using Shakespeare, Mary Shelley, Orwell, Vonnegut?

“Nah,” Lui replied.

No one I spoke to had an English teacher like this, and a couple of interviewees who grew up in the Islands told me this approach would have been a waste of time. Physical punishment was the norm back home, said Siose, 21, who moved to New Zealand from Samoa when he was 17, so the lack of discipline in New Zealand classrooms came as a shock. “Kids were naughty, disrespecting the teacher,” he said, “whereas back in the Islands we would’ve gotten a hiding from the teacher if we disrespected them.”

Because so many of the most difficult kids have these backgrounds, they only respond to violence and hierarchy, Michael, a 28-year-old mechanic, told me: teachers can’t “beat them up” so aren’t worth listening to, and a softly-softly method doesn’t cut it with those students. “If you come with an ‘I come in peace’ approach,” he said, “they’ll eat you alive.”

It’s not just the teachers who get eaten alive, either. A few interviewees told me there was a culture of bullying at their schools so brutal it prohibited them, and everyone else, from speaking in class—anyone brave/foolhardy enough to ask or answer a question, saying something “dumb” or “fobbing out” in the process, would become an immediate social pariah. “They start laughing or mocking you for the rest of the day,” Siose said. “They stop hanging out with you. They say ‘go back to your country, go back to the islands.’”

‘I’ve heard of Shakespeare off movies and stuff but I don’t know anything about him’

When I asked my interviewees whether they studied a novel in English class, two could recall them off the top of their heads: Malia, a 29-year-old art teacher, said her class was assigned Holes, and Joseph’s class did The Hunger Games; both young-adult fare. Four of my interviewees said they studied a novel but couldn’t remember the name, and Lui told me he’s pretty sure they never studied a novel at all.

Any Shakespeare?

“Nah, nah, I never studied Shakespeare,” Joseph said. “Like, I’ve heard of Shakespeare off movies and stuff but I don’t know anything about him.”

Most of my interviewees echoed this answer, but Malia and Tina, a 30-year-old healthcare worker, said they were exposed to Shakespeare in the following way: the teacher would print off a single short section on an A4 handout for students to learn and quote in exams (The Taming of the Shrew and Othello respectively). But there was little help deciphering the Early Modern English, so their interest was never piqued.

Even among interviewees who were assigned texts in class, I was repeatedly told that pretty much no one actually read them. Five interviewees said they weren’t allowed to take the novels they were reading in class home—“it’s a decile one school, you won’t get your copies back,” Lui laughed—which meant reading time was limited to whatever quiet moments they could grab in English class. The problem is, there were almost no quiet moments.

‘I don’t wanna get too graphic; it’s like vigorous face-fucking. He’s showing everyone’

Most of my interviewees said their classrooms were informally arranged according to enthusiasm levels: “all the dorks at the front,” as Joseph put it, then the middle students in the middle. At the back “was us,” Joseph continued. Who’s us? “The fucken loud ones.”

The Fucken Loud Ones were a constant drain on the rest of the class, everyone told me, distracting the Dorks and Middles and sapping the teachers’ attention. Whether it was fights, girls crying about problems at home, or loud laughing and chatter, there was always a cacophony in class. “I don’t remember one class being smooth,” Lui said.

Often teachers would give up and leave the most disruptive kids to their own devices, which meant leaving them to their, well, devices. “I discovered some weird porn in high school, off this fob kid’s phone who could barely speak English,” Joseph said. “I don’t wanna get too graphic; it’s like vigorous face-fucking. He’s showing everyone.”

This was totally quotidian, several interviewees told me: distracted students would be absorbed in “porn and Chris Brown videos”, according to Lui, or watching ASMR videos on their laptops, according to Francesca, a 17-year-old still in high school. Students in Francesca’s class were allowed to use laptops in class; everyone I spoke to said phones were banned but teachers were powerless to enforce the ban and/or uninterested in really trying.

And now, of course, there’s AI. What little incentive there was to actually read the assigned texts has almost completely vanished, Francesca told me, now that students can use ChatGPT to summarise chapters and spit out passable essays. “Everyone uses AI now,” she said. “It’s faster than having to read the whole thing. I don't think there’s a lot of research or anything that the students actually do—it’s so unfair because they’ll be getting high grades, and I actually try, and I’ll be getting like a C or B.”

Francesa said her teachers are totally resigned to the ChatGPT takeover, and merely encourage students to put the AI-generated essays into something resembling their own words.

“There’s nothing they can do about it,” she added.

*All the first names of my interviewees have been changed so they felt free to speak frankly. The other details are unchanged.

I grew up in a polar opposite environment (Decile 10, North Shore, Private School), and reading this made me so sad. My little nephews absolutely love being read to every night and the idea that children don't grow up with that is just sad. I wish everyone had the same access to education. Goes to show just being physically in the class is meaningless if children aren't actually learning anything.

Thanks so much Maddie. Bleak. Especially the last part.