Never, ever let the machine draft your emails

Friendly reminder that I’m incandescent with rage.

Recently I witnessed the castration of a furious, spirited man. Maybe you did too. The man’s name was Dale; a character in an ad for Apple Intelligence, an AI-powered writing tool that makes your emails sound Friendly, Professional or Concise with the click of a button. When we encounter Dale, he’s seething, positively ropeable, about the petty theft of his pudding from the office fridge. It’s clear we’re meant to read Dale as being a prissy little bitch, with his stiff collar, neat moustache, and fussy mannerisms, but there’s nothing limp-wristed about the tirade he bashes out on his MacBook keyboard. “To the inconsiderate monster who has been stealing my pudding,” he begins, “I hope your conscience eats at you like you have eaten my pudding.”

Dale pauses doubtfully before clicking send, glancing at a ‘FIND YOUR KINDNESS’ T-shirt on a nearby teddy bear. After he selects Apple Intelligence’s Friendly mode, Dale’s searing tirade is rendered into limp corporate speak. The new tone-adjusted message kicks off with “Hey there”, neuters lines like “That pudding was my only light in an otherwise bleak corporate existence” into “You see, snacks are a big deal in our company”, and rounds off with an insipid, “Thanks for your understanding.” His pudding is returned by the woman who stole it. Dale eats an ecstatic mouthful. He ‘wins’.

The ad is meant to be funny, but there’s no irony whatsoever about that last point: that by capitulating to Friendly mode, Dale ‘wins’. Any red-blooded viewer can see his lifeforce being drained from his eye sockets; you get the sense this short film is winding up to a Clockwork Orange-style meditation on the creepiness of social engineering wrought by AI. But it isn’t. It’s an advertisement for AI. It isn’t meant to be blood-curdling, it’s meant to have you laughing all the way to the Apple Intelligence software update: the sooner you start Friendlifying your emails, the better! That this bland, eunuch prose is actually good is taken as read.

I assume everyone but the most bloodless tech shills views this development as a horror, but I’m not sure: I don’t go on social media anymore, so if there was a wave of backlash, I missed it. But waves of backlash give me no comfort these days anyway. This isn’t my first rodeo.

My first rodeo was in 2018. Smart Replies — those three brisk, easy-click, AI-generated reply options autopopulated under certain emails — were being rolled out as standard on all Gmail accounts (as well as the Smart Compose function, which predicts the end of your sentence as you type). Smart Replies were widely derided as insulting and creepy, on social and traditional media alike, and their jaunty, discordant tone roundly mocked.

Some journalists briefly grappled with the broader interrelational, intellectual, and spiritual stakes of giving in to this technology. “I have wondered whether saving a few seconds of not having to type ‘ok, sounds good’ is worth letting a robot mediate my interactions with other humans,” wrote Mashable reporter Rachel Kraus. “Or if the impulse to hit a button instead of form a thought could in some way stymie my own expression, even in rote communications.”

In the end, though, Kraus said she couldn’t decide. Elsewhere, resignation prevailed. In 2018, the Wall Street Journal reported that Smart Replies already constituted 10 percent of all messages sent over Gmail. After deriding them as inhuman in the New Yorker, Rachel Syme wrote: “At some point, I started giving in to the Smart Reply robots from time to time, and something strange happened. I didn’t hate it.”

Reading back over this coverage today, I find the lack of conviction maddening. Over and over, writers betrayed an intuition that something was deeply wrong with Smart Replies — that the machines were starting to remodel us in their own “ghastly image” — then they cracked a weak joke, shrugged and moved on, or started using them. None of these writers were shrill or hysterical, none made an urgent moral case, none raised their voice. None of them, in other words, sounded like Dale. And now Dale has no balls.

Why are so many people so sanguine about the robot takeover of our emails? Probably because of how passionately we loathe our inboxes: the relentless onslaught of messages (74 per day, on average), their tone of false cheer, and the fact that so many come from people we hold in mild contempt — managers, real estate agents, spin doctors, if they come from people at all — yet we’re obliged to spend huge chunks of our allegedly wild and precious lives dealing with them. Even for people creeped out by the prospect of using AI tools like Smart Replies, ChatGPT and Apple Intelligence to compose their communication, the offer sounds too good to refuse.

But it was obvious from the outset that the machine wouldn’t stop at the domain of work, and would soon come for the domain of love. Here’s the British writer Sam Kriss at the end of 2023, with a half-joking prediction that robots would soon take over our more intimate online realms:

You don’t hang out with your friends any more, but you have a group chat. Increasingly, your messages to your group chat will be written by AI. The machines will communicate for everyone in the same friendly, even tone, and everyone’s group chat will contain the same roster of mildly funny memes. You will look at them and feel nothing, and push a button to generate your response. Ha! That’s so funny, Dave! You’re the Meme King!

You don’t meet people any more, you use online dating. Increasingly, your conversations with prospective lovers will be written by AI. Your machine will generate banalities at her machine, about tacos and The Office and pineapple on pizza, and her machine will do the same, until it’s time for her to autogenerate a nude. You will look at it and feel nothing, and push a button to generate a response. Wow you’re so sexy. And then, having never spoken to each other before, you will never speak to each other again.

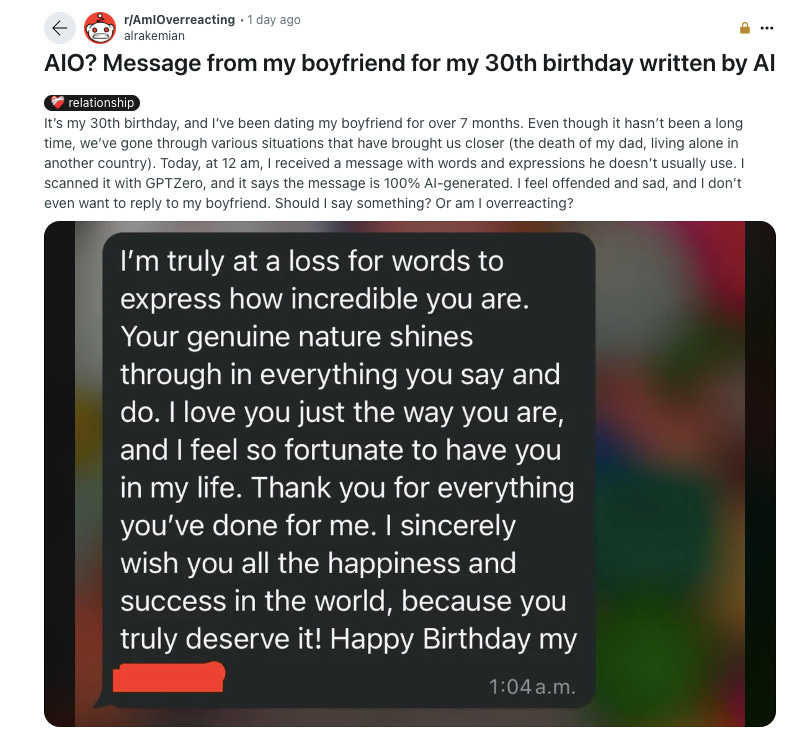

Now, we have real-time examples of this exact nightmare unfolding. Last week, for instance, a woman took to Reddit to share a screenshot of a ‘heartfelt’ text message her boyfriend sent her for her birthday, clearly generated in its entirety by AI. She reports, quite naturally, feeling offended and sad. But note her primary inquiry to the Reddit forum: am I overreacting? For some commenters in the thread, the answer is yes.

How did we slide into this “boring dystopia”, this “unlivable techno-dump”, in which robots communicate for us while we sit by, drooling? And why didn’t we resist?

Let’s set aside people who truly see no problem with the birthday message above, the AI defenders wheeeee-ing down the slide to the techno-dump. Let’s consider the moderates, cautiously gripping the sides. When I listen to them speak, they insist on two key points: one is that any brain damage caused by using AI communication tools can be safely contained by limiting its use to certain circumstances: I only use Smart Replies when I’m really busy. I use ChatGPT to draft my work emails, but I’d never use it to text a friend.

Two, they insist that human qualities ultimately prevail: AI gives me a draft, which I tweak as I see fit. All it does is help me get over the inertia and dread of facing a blank compose box, then my human judgement and skill kick in. I still care about the person at the receiving end of my message.

This is all wrong. To assume nothing is lost when humans are freed from the inertia and dread of facing a blank compose box; to believe you can still care for people after you stop performing the small, quotidian actions that constitute care; to delude yourself that your good qualities will remain stable if you give up the very work that forges your character: it’s all wrong. There is no safe container for AI communication, no acceptable use case, not even low-stakes work emails to people you hate. Make a habit of using these tools, and not only will all your relationships become husks, you yourself will become a husk. The stakes couldn't be higher. To see why, we need to return to Dale’s office.

Dale is an AI moderate. He would never use ChatGPT to draft a lover’s birthday text, but he’s happy using Apple Intelligence to smooth out aggro work emails about stolen puddings, and he makes frequent use of Smart Replies. He has to! He gets so many emails.

Dale works as a communications officer for a large logistics and transport corporation — a day job he hates, with coworkers every bit as tedious as the work — but on the side, he helps edit a small literary magazine, work that truly sets his heart ablaze. Dale has three Gmail addresses, one for his day job, one for the magazine, and one personal, but to streamline his communications he has them all directed to a single inbox — the inbox he’s facing with increasing dread on this Tuesday morning in the office.

Paralysed by 74 new messages, plus 26 read emails from previous days and weeks he’s determined require a response, Dale begins answering around a third of the new emails using Smart Replies — the low-stakes stuff: unsolicited emails from publicists and real estate agents, trivial life admin, pointless to-and-fros with his manager. He’s aware, somewhere at the back of his mind, that this embroils him in a Whack-a-mole game of ever-proliferating emails: the faster he replies, the more dizzying the game becomes. But he hits the Smart Reply button anyway, batting away a nagging set of questions at the same time: why are my manager and I swapping Smart Replies when we work in the same room? Why don’t people pick up the phone anymore? Why are some of the best minds of my generation sending pointless emails all day long? Why is pudding my only light in an otherwise bleak corporate existence? Why am I living like this? And why don’t I resist?

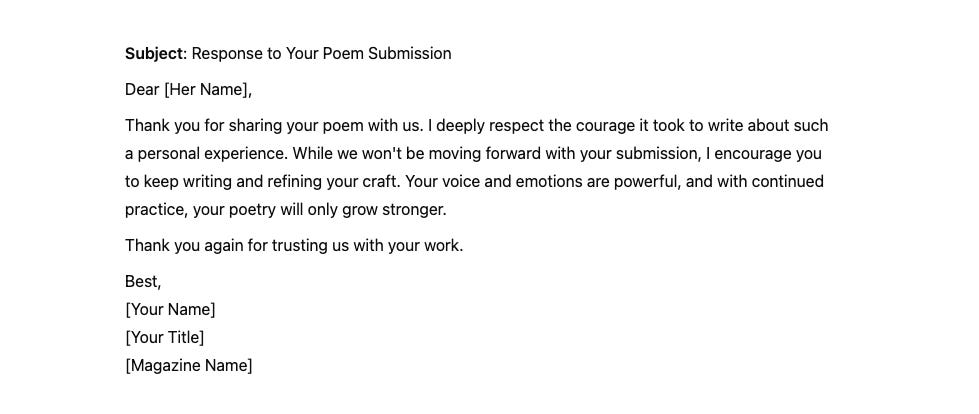

Existential questions swatted away, Dale turns with dread to the 26 read emails languishing in his inbox. These are thorny emails of much greater consequence, the ones Smart Replies can’t help him with. He reopens one containing a poem by an unknown young woman submitted for publication by the magazine he edits. The poem lays bare a deep personal wound; detailing the woman’s date rape at age 17. The poem is overwrought, unpublishable, just plain bad. This woman had such guts to pen something so raw, but she’s got so much to learn about crafting poetry. Dale hopes she keeps writing. He needs to reject her submission, but he wants to do so without crushing her spirit.

The other 25 emails are similarly sensitive and difficult, for their own set of reasons, and Dale’s decided he needs to answer them all today. But he doesn’t know what to say. He can’t get started. He’s paralysed. The clock is ticking. He needs help.

Dale considers that ChatGPT could move him past this impasse. He feels uneasy about using AI to deal with sensitive emails: the last thing he wants is to end up like the dean of Vanderbilt University, sending a platitudinous, AI-generated email in the wake of a mass shooting. But as the machine spits out a surprisingly polite and humane set of words for Dale to lightly edit and send off to the aspiring poet, his trepidation lifts, and another set of questions at the back of his mind stops nagging so loudly, namely: who is this person that’s emailed me, and what do I owe them? Is it my job to save a new writer from the sting of rejection? Is it worse to be blunt or fake? What are the costs of saying the wrong thing? What are the costs of always being paralysed by fear of saying the wrong thing? What should I say?

Why is the AI-generated rejection letter or birthday text so dehumanising? Think about what it means to treat someone well: fundamentally, it involves considering who they are, what they might want and need, and whether you can help. This can be difficult, maddening work, because other people are such puzzles: strangers are a mystery, obviously, but even with loved ones, all we ultimately have to go on is some theory of mind and a few clues about their ever-changing set of likes and dislikes. So ‘considering’ is the operative word: we have cliches like “it’s the thought that counts” because we recognise that the process of thinking about, considering, puzzling over another person is what actually constitutes care, not the flashy gift or perfectly crafted message that results. When you outsource the thinking to AI, you outsource the care. Your communication becomes empty, and your relationships hollow out.

But so do you. Whenever you are facing a blank compose box, filled with dread and inertia, you are being presented with a small, quotidian opportunity to strengthen your character. Whether it’s a birthday text, rejection letter, or quick reply to a dumb message from your manager, the resistance is always telling you something useful. This is the stuff that really matters. This shit doesn’t matter at all.

It takes courage to decline your manager’s waste-of-time request. It takes tact and sensitivity to draft a good rejection letter. It takes wisdom and perspective to decide to ignore unsolicited emails from publicists and real estate agents. When you use AI as a crutch, always at the ready with a suitable set of words — when you bypass the resistance and bat away those deep nagging questions — you deprive yourself of an opportunity to be brave, tactful, and wise. Do this over and over, and your bravery, tact and wisdom will atrophy. Your character will corrode.

This is why AI communication tools can’t be safely contained by limiting their use to certain circumstances, like bullshit work emails: there is no sphere of your life where this chipping away at your character doesn’t cost you. Making a habit of using these tools also means missing a vital lesson, which is that failure is salutary. It moulds you beautifully to fuck up and say the wrong thing, or fail to say anything at all, and notice the pain this causes. Or the surprising lack of pain it causes — the maddening array of responses it elicits in different people. Alice respects a prompt, blunt rejection email; Miles goes to pieces over it. What do you do with this? I send Alice prompt, blunt rejection emails, and spend weeks crafting ornate and soothing missives to Miles. Or: I send prompt, blunt rejection emails, whoever you are, come what may, because that is who I am.

Machines have a place, and there is drudge work we should hand to them. Let them wash your filthy clothes and drill holes in hard earth. But not this. Never this.